On August 23, 2019, over 210,000 Hongkongers joined hands in a 60 kilometer human chain to protest police violence and to demand democratic reforms. This human chain, called the Hong Kong Way, took place on the 30th anniversary of another human chain protest—the Baltic Way of 1989—in which approximately two million Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians formed a 690 kilometer human chain across the three countries to protest the Soviet occupation. Iverson Ng, an Estonian-based Hongkonger, tells the story.

TRANSCRIPT

Colin Gioia Connors: The following episode contains descriptions of police violence and suicide. Please use discretion.

Iverson Ng: I’m really embarrassed by the fact that I was in Estonia the whole time. So I was— You know, when I think back I should have done more. I should have been the person who organized the human chain, but however I was psychologically very stressed back then. I didn’t know what to do. It was actually a very existential struggle about what I should have done. I thought about going back to Hong Kong and to fight, but I decided not to do that. I decided to write opinion articles to raise awareness in Estonia and other European countries.

[*Intro music starts*]

Colin: Welcome to Crossing North: a podcast where we learn from Nordic and Baltic artists, scholars, and community members to better understand our world, our communities, and ourselves. Coming to you from the Scandinavian Studies Department and Baltic Studies Program at the University of Washington in Seattle, I’m your host Colin Gioia Connors.

[*Intro music ends*]

Iverson: Hello everyone, my name is Iverson Ng. I'm a columnist based in Estonia and I have been living in Estonia for five years and originally I'm from Hong Kong.

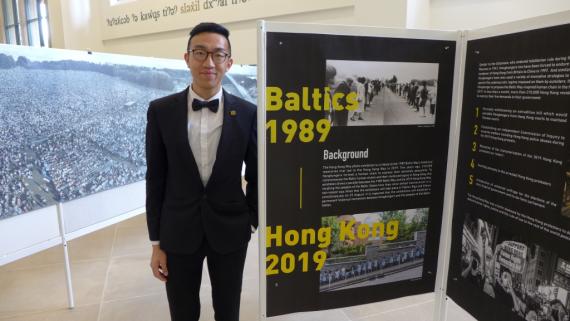

Colin: Iverson Ng came to Seattle last spring to attend the annual conference for the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies, and to display an exhibit at the UW libraries about the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests of 2019. The exhibit highlighted one protest event in particular: On August 23, 2019, over 210,000 Hongkongers joined hands in a 60 kilometer human chain to protest police violence and to demand democratic reforms. This human chain, called the Hong Kong Way, took place on the 30th anniversary of another human chain protest—the Baltic Way of 1989—in which approximately two million Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians formed a 690 kilometer human chain across the three countries to protest the Soviet occupation.

The Baltic Way of 1989 was itself an anniversary. Its organizers chose the date of August 23 to raise awareness of and to protest the Soviet-Nazi nonaggression treaty’s secret protocols, which had been agreed upon exactly 50 years before, on August 23, 1939. In those secret protocols, Soviet and Nazi leaders agreed that Germany would invade and occupy western Poland, while the Soviet Union would invade and occupy eastern Poland and the Baltic countries. The two empires executed the plan, and less than a year later, in 1940, formal Soviet annexation of the Baltic states was complete. The Baltic states remained under Soviet control, without local democratic institutions, for the next half century.

Less than a year after the 1989 Baltic Way protest, the three Baltic states declared their independence on the basis that the Nazi-Soviet secret protocols were illegal and null, and by 1991 their independence was recognized internationally.

Although separated by 30 years and half a globe apart, the 1989 Baltic Way protest and the 2019 Hong Kong Way protest reveal a common truth between the Baltics and Hong Kong: two peoples fighting for liberal democracy and autonomy from illiberal, authoritarian communist oppression.

Iverson: I think the biggest motivation for me is that I somehow project my Hong Kong identity into Estonia, where I see Estonia is a small country of 1.3 million inhabitants, where it has a huge neighbor Russia, and the size is actually not comparable between them at all. And when you look into Hong Kong and China, it is a similar story, even though officially Hong Kong is part of China. But because of what I explained about the differences between Hong Kong's autonomous system, its British tradition, as well as the sense of fair play that it has, Hong Kong is quite differentiated from China and that's why in a lot of ways that Hongkongers see ourselves as Hongkongers but not Chinese. So getting back to that motivation part, it’s about the idea that I always struggled with my Hong Kong identity because when I was in Denmark in 2015, I was saying that, “Well, I'm a Hongkonger. I'm from Hong Kong,” and people don't understand and ask like, “So, Hong Kong is part of China, so why do you think you're not Chinese?” And I had to explain to myself time and time again. And thanks to all these protesters in 2019, I think we have shown the world that—why Hongkongers are Hongkongers—and we are willing to pay everything for the identity that we will hold dear to. And I think that is something I would project myself to Estonia, because Estonia is clearly a nation, a country, part of the NATO and the EU. So it is important to see that being an Estonian migrant, that it also gives me a sense of belonging, that I'm part of the Estonian society, even though I'm from a very different ethnic background compared to Estonians, or, let's say, Russian speaking Estonians. But then I do think that culturally I'm quite integrated to the country. I'm accepted by not just my close friends around me but also the communities and also the whole country as a whole. People understand that I'm fighting for Hong Kong while being an Estonian migrant. So all these factors combined, it makes me feel that I'm part of this country and I'm also proud of my origin as a Hongkonger.

Colin: The liberal values to which Iverson refers—autonomy, democracy, and an impartial judiciary—are a consequence of Hong Kong’s history as a British colony. The colony lasted from 1841 to 1997, when Britain ceded the colony to China. Under the terms of the treaty, China agreed to preserve the autonomy of Hong Kong’s economic, judicial, and democratic institutions under the “one country, two systems” model. China, however, broke the terms of the treaty, and in 2014 they passed a law requiring candidates for the office of Chief Executive in Hong Kong to be pre-approved by the Chinese Communist Party before running for office. Over 100,000 Hongkongers protested the change by occupying streets and government buildings, and they were met with police violence. Protesters shielded themselves from tear gas and rubber bullets with umbrellas, giving rise to the name “The Umbrella Revolution.” Iverson was a student journalist in 2014 and he covered the protests and police violence.

Iverson: Yes, in 2014 I was a student journalist who spent most of my time in the 79 day occupation movement in Hong Kong.

Hongkongers demanded to have universal suffrage. It was in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s white paper on the "one country, two systems" in which they rejected the notion of having a direct election for Hongkongers to elect its future leader—the “chief executive,” we call it in Hong Kong. It is more like a de-facto head of state and it's kind of like a prime minister with similar powers. But it's the head of the Hong Kong government. So because there were scholars who proposed the civil disobedience notion, similar to a lot of civil rights activists in the past, and that's why Hongkongers, given the threat by the tear gas fired by the riot police on the 28th of September 2014, Hongkongers started to occupy the main thoroughfares of the Hong Kong financial district so that they wanted to paralyze the financial center of Hong Kong to negotiate with the Hong Kong government. The whole occupation lasted for almost 3 months, and most of the time I was there.

So I learned about the rise and fall of the Hong Kong nonviolent protest. And that was the time when I started to see that I couldn't really think of any positive future scenario of the future of Hong Kong and I kind of because of that decided to leave the city for good and start a new life in Estonia.

Colin: The 2014 protests succeeded in galvanizing the political will of Hongkongers and brought international attention to their situation, but the protests failed to achieve the democratic reforms they sought. The Beijing-controlled government made zero concessions, and they arrested the protest’s leaders. Iverson went abroad, first as an exchange student to Denmark, and then, after making several Estonian friends, he moved to Tallinn in 2017 to begin a master’s program in EU-Russian relations. Iverson was thus abroad when protests erupted again in Hong Kong in 2019. Although not working as a journalist in 2019, he followed the events closely. Iverson explains the events that led to the protests in a UW Scandinavian Studies class:

Iverson: Basically, in 2019 there was a Hong Kong couple—the boyfriend killed the girlfriend in Taiwan. And it's a criminal offense, but then there was no extradition treaty between Taiwan and Hong Kong. So, it all sounds logical that the Hong Kong government requested to have an extradition treaty so that they could transfer the suspected criminal from Taiwan to Hong Kong. It all sounds logical. But you think about what I just said about the sovereignty issue that Hong Kong is legally part of the People's Republic of China. So that means that even though Hong Kong has its own common law jurisdiction and independent judiciary to some sense—it is used to act as a firewall, separating Hong Kong from mainland China—but then with that proposal, that would mean that the extradition between Taiwan and Hong Kong, mainland China, and Macau would be possible.

Colin: The extradition bill meant that any Hongkonger, say for example, anyone arrested at a protest, could be extradited to mainland China to be tried in Chinese courts. Whereas Hongkongers expect a fair trial in Hong Kong courts, they have little hope of fairness in Chinese courts, where the conviction rate is 99.9%. The bill threatened Hong Kong’s autonomy and the freedom of its citizens, and once again, Hongkongers took to the streets in protest. They had five demands: first, they demanded the government rescind the extradition bill, second, they demanded that the government stop referring to protesters as rioters, third, they demanded that the government release all protesters who had been arrested and drop the charges against them, fourth, they demanded the government establish an independent investigation of police brutality, and fifth, they demanded universal suffrage and the resignation of the chief executive.

Iverson: We talked about the peaceful protest— One million people came out; the government didn't listen. There were clashes, and then the government wasn't listening. And there were 2 million out of 7.4 million Hongkongers who showed up to demonstrate their anger. So, it was an extension of the 2014 Umbrella Revolution, because back then, 2014, we were talking about one night and 87 canisters of tear gas. But then in the 2019 Hong Kong protests, we were talking about 16,000 rounds of tear gas and 10,000 rounds of rubber bullets over the six months of protest. So you can imagine how frequent it was. Hong Kong literally became a city of tear gas and rubber bullets.

Colin: In the face of escalating police violence, some 2019 protesters decided to fight back against the police. An Academy Award-nominated documentary film called Do Not Split documents their efforts. The film shows many examples of police brutality leveled indiscriminately against protesters and bystanders alike. In one scene, police run down a sidewalk and plow over a pedestrian. His head hits the pavement and blood pours down his face as he cries out his innocence. The police mock him as they move on. Paramedics rush the man to an ambulance, and he complains to witnessing journalists that the police have made it unsafe to go outside. Later, the film shows police targeting the filmmakers. They charge the camera with batons drawn, ready to strike. The camera shakes as the filmmakers flee, and the film cuts to another scene. In another protest event, a medic is shot in the face with a bean-bag round. Her eye ruptures. Over and over, the film documents instances of the police firing tear gas and rubber bullets into crowds. But unlike in 2014, now protesters retaliate, throwing molotov cocktails at the police as they attempt to hold their ground and avoid being arrested and beaten. “Without you we were all peaceful” an old man shouts at the police.

Iverson: And as for other challenges for journalists in Hong Kong, is that journalists are like the referees. So in a football match, for example, you wouldn't attack the referees. And that was what the riot police was doing with countless evidence, and also different, let's say, instances that show the Hong Kong police was actually targeting the journalists not to allow them to report what was happening, to stop the momentum of the Hong Kong movement. But I can tell you that at some point it was, actually, almost impossible for journalists to be completely objective, because if you became the victim, you became the target, then you actually couldn't really stay away from the side of understanding what was happening with the protesters, because they were the ones who protected you and the police were trying to attack you in all means.

Colin: The rise in violent action was also a response to the perceived ineffectiveness of the nonviolent protests in 2014. How do you make a government listen to what it does not want to hear? The different tactics employed during the six months of protest in 2019 speak to the evolution of protests in Hong Kong, and to the commitment of Hongkongers to preserving democracy. Some protesters paid the ultimate price.

Iverson: Here and then, between, we had quite historically over a dozen Hongkongers who committed suicide to protest against the government. So you can see how much frustrations they were, because in any social movement it is not very common to see people literally jumping off from the buildings, using their lives to protest against the government. It didn't happen very frequently in the world, and in Hong Kong it was the first time that we had a wave of Hongkongers, you know, using their lives for such a cause.

Colin: Chinese media presented the political crisis as a mental health crisis that was afflicting Hong Kong’s youth. This framing was repeated in international journalism outlets, and the discourse had many protesters afraid that if they were arrested and extradited to China, their forced disappearances might be covered up as suicides.

Iverson: I think the biggest challenge is that there is propaganda. And, you know, people who are propagandizing, they are trying to portray that there is no objective truth, that there's no fact, [that] facts are relative. And by doing so, they are denying what is actually happening on the ground in Hong Kong back then in 2019.

So for the statements you mentioned, there were statements that people really declare that, not just virtually, but also like physically printing papers, you know, putting that in their pockets, that you know, “I'm not going to commit suicide. If I disappear, then maybe something is wrong with me.” Then I saw a lot of friends of mine actually did that on their social media updates as well. So, they were trying to show that, “Well, some kind of horrible things are happening in Hong Kong and we are too vulnerable to protect ourselves, and please use this piece of information to protect us.” And I think that was what I was getting at that time.

And there is, of course, some elements of mental health challenges, because if you are in a highly stressed environment on a nonstop 24/7 daily basis and the movement lasts for six months and it is a quite popular belief that you have all these messages around you flowing all the time about, you know, riot police, how they attack your friends, family, arresting the people around you, someone you care about—of course there would be some mental issues with the extensive local and international news coverage. But then what I want to emphasize, however, is that it is not just about mental health issues, it’s more about how high of a price that Hongkongers would like to pay for the future of the future Hongkongers before 2047, because we thought about what kind of world that our kids want to live in in the future. And a lot of people thought about that and made the decision that they had to be the ones who sacrificed themselves and hopefully that could get a momentum. But actually it didn't work out very well with those incidents.

Colin: Hongkongers disagreed about the best form of protest. In the face of such violence, is it better to endure injury, arrest, and death, or to fight back? There was no clear consensus, but the one thing Hongkongers agreed on was not to condemn another’s form of protest. “Do Not Split” became a mantra of solidarity among the 2019 protestors. Despite differences in protest philosophy and action, protesters reminded one another with these words to focus their criticism on the Chinese Communist Party and the police, not on one another.

The 2019 protests adapted in other ways to the increasingly combative tactics of the Hong Kong police. Protesters used encrypted social media apps to communicate when and where to gather, and when and where to flee as riot police approached. The protesters were mobile and no longer focused on occupying a single location. As Iverson explains, “no big stage” was the second mantra developed by protesters.

Iverson: It's about decentralization because in 2014 there were, let's say, Hong Kong representatives or student representatives, representatives from the political parties in Hong Kong, and once they were arrested, it kind of affected the approaches and tactics. And we said there was a so-called “big stage.” It's like the centralizing authorities for coordinating with the Hong Kong movement in 2014. And people realized that you really have to decentralize so that the movement will last much longer, and actually it kind of worked in 2019. And it is all about what Bruce Lee said, “Be water, my friend,” that Hong Kong protesters were moving like fluid so they're not getting stuck in one position, and that's why they had limited success in the very beginning of the protest. And also the tactics deployed in the summer of 2019—the Hong Kong Way was only one of the tactics. Other tactics were also including the occupation of the airport, and trying not to go to school, boycotting classes, and then calling for general strike and so on and so forth, or even trying to have protests in all 18 districts in Hong Kong. So these kinds of things, I believe that some of them were drawn from the lessons in 2014.

Colin: Iverson mentions Bruce Lee as a hero for Hongkongers and a hero for Seattleites. Bruce Lee was an American-born Hongkonger martial artist and actor who studied drama and philosophy at the University of Washington in the early 1960s. He is easily UW’s most famous alumnus, and every day hundreds of students walk up the stairs where his trademark silhouette is painted in the Odegaard Undergraduate Library, underscoring a historic connection between UW students and Hongkongers. Bruce Lee is remembered for his many philosophic quotes related to his fighting and acting careers, the most famous of which was first spoken in a character role in a 1971 episode of the American tv-series Longstreet, and later repeated that year in a now famous interview on the The Pierre Berton Show.

Bruce Lee: I said “Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless like water. Now you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it into a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

These words have inspired countless individuals across the globe, and they inspired Bruce Lee’s compatriots in the protests of 2019. And on August 23, the shape the protest took was that of a 60km-long human chain. The idea for a human chain protest on the anniversary of the Baltic Way was proposed by an anonymous Tallinn-based Hongkonger on a Cantonese social media site. Within a month, 210,000 Hongkongers showed up and held hands in a line that crisscrossed every corner of Hong Kong.

Iverson: Within the context of the Hong Kong human chain, Hongkongers were using a platform called Telegram. It's an encrypted messaging platform, so it was entirely organic. There was, like, no central leader to lead that organization. They were having, like, regional groups to arrange for the allocation of volunteers. You know, where you have to stand at what time? How are you going to do that? And in the clip, you actually saw that it took place in the mountains. It also took place when the traffic light turned green, and then, you know, people showed up and then they dispersed. So there were a lot of things about that. So it was actually a very historical moment, not just for Hongkongers, but also for the people of the Baltic states to extend their democratic memories stretching from 1989 with the Baltic Way to the Hong Kong Way inspired by the people of the Baltic states.

Colin: Like the human chain organized in the Baltics in 1989, the Hong Kong Way was a significant moment in a growing movement. The nonviolence of the protesters was an irrefutable counter-argument to the Chinese propaganda that categorized protesters as terrorists. The lack of a center made it impossible for the police to break the protest. And the human chain bolstered the resolve of every individual who formed a link in that chain, who looked up and down that line, and did the math to multiply the number of supporters needed to stretch 60km, all of them people who were willing to show up and risk themselves in the name of democracy.

That momentum carried forward as the protests took a new form every night. On October 28, the government finally withdrew the extradition bill. But with only one of the five demands met, the protests continued in November, December, and into the new year of 2020, when the emergence of the coronavirus, SARS-covid-2, brought the protests to an end. Hongkongers who had not forgotten the 2003 SARS epidemic voluntarily adopted mask-wearing and self-isolation protocols. But as Hongkongers sheltered in place, the Beijing controlled government got to work to create even more draconian laws. This included the national security law of 2020 that criminalized any form of protest, and a new law in 2021 that extended the requirement for Communist Party pre-approval for to all legislative candidates. Despite these defeats, Iverson remains hopeful:

Iverson: And probably I will be a bit brief with the last one, it's more touching upon the current situation. And the last principle of the 2019 Hong Kong protest is that we want to “blossom everywhere.” That means that you can kill the protests in Hong Kong, but you can't kill all the Hongkongers in the world, that as long as we have a Hongkonger somewhere in a corner of the world, then we have Hong Kong. That means after 2019 we had an extraterritorial national security law that would effectively put anyone in jail on on any place on the planet, and even outside the planet, according to that law that as long as you are criticizing the Hong Kong or Chinese government, or you know, just speaking out, you're—just like what I'm doing right now—you would be possibly violating the law. And you can be violating the law abroad regardless of our nationality. So it doesn't matter whether you are European Union national or you are an American citizen. Doesn't matter, that if you go to Hong Kong, if they think—if they think—that you have violated the law, then you will get jailed for up to life imprisonment in mainland China. And the first case was nine years in prison.It was a man who showed the flag of “liberate Hong Kong revolution for our times.” A man was driving a motorcycle into the Hong Kong police force, but he was charged for secession and also, you know, with the idea of, you know, pushing for Hong Kong independence, and now serving nine years in jail.

Colin: When I meet Iverson at the university for the unveiling of his exhibit at the Suzzallo-Allen Library, we discover that the exhibit has been defaced with pro-Chinese propaganda. Paper had been taped to the exhibit that read “Think Critically. Respect Diversity. Say NO to hate, violence, and unrest. Make the world a better place for all mankind.” As Iverson took it down, he commented on the paradox of the propaganda’s appeal to liberal values while it advocates for an illiberal regime.

Iverson: Yes, I do see why you are confused with the Chinese approach, as a lot of European elites are also having troubles in understanding the intentions of China. So, the example of Hong Kong is actually a very classic demonstration of how China is trying to weigh in the, let's say, political gains and the economic benefits. So, for any rational actors, they would actually think about, let's say, being cautious about what kind of courses they're paying and what kind of outcomes they will be receiving. But for the Chinese Communist Party, when you have to make them choose between the economic benefits and the political gain, they are always prioritizing the political gains, that is, the survival of the Chinese Communist regime. The very existence of Hong Kong's autonomy is actually for China a threat for them, because Hongkongers are always so different from the Chinese Communist Party, that we always believe in the rule of law, democracy, and basic freedoms, as well as human rights. These elements do not exist in mainland China. And that's why when we have all these clashes of ideologies, China is always choosing the irrational path, that is, to make sure that they can secure their political gains no matter what. And this is actually hurting China's economy, and the global economy, and, of course, the livelihood of Hongkongers. But this is what they are doing, and that is what they will continue to do in a range of other issues.

And I think I will take this opportunity for those who are listening to this podcast: don't give up Hong Kong and don't give up Hongkongers. Maybe you would think that after what you have been following with the development in Hong Kong, it sounds and looks very depressing, and that a lot of people, a lot of international supporters are having Hong Kong fatigue. But on the other hand, you have to look into, for example, we have quite a lot of Hongkongers living in Seattle—some are university students and some are settled, but they're not giving up for their homeland Hong Kong. And I think you shouldn't give it up, because you shouldn't give up, because Hong Kong is not about just Hong Kong’s territory. It’s more about how we believe in the free world and how much we want to tell the world that we are part of this global Democratic alliance, and we are willing to pay for everything, no matter how high the cost is. We want to defend not just the freedom for Hongkongers, but also for the rest of the world, for the rest of the world's freedom fighters, and people who are living in the US. So I hope that if you have a chance, do talk to your Hong Kong friends. And if you don't have Hong Kong friends, try to make some Hong Kong friends, and I'm sure that you will start believing in idealism and in an ideal world where democracies will triumph against the authoritarian regimes in the world. Thank you.

[*Outro music starts*]

Colin: Crossing North is a production of the Scandinavian Studies Department and Baltic Studies Program at the University of Washington in Seattle. Today’s episode was written, edited, and produced by me, Colin Gioia Connors. Today’s music was used with permission by Kristján Hrannar Pálsson. Links to his music can be found in the show notes for this episode or on our website. Visit scandinavian.washington.edu to learn more about the podcast and other exciting projects hosted by the Scandinavian Studies Department. If you are a current or prospective student, consider taking a course or declaring a major. You can find complete course listings for the Scandinavian Studies Department and Baltic Studies Program at scandinavian.washington.edu. Once again, that’s scandinavian.washington.edu.

[*Outro music ends*]

SHOW NOTES

Release Date: February 13, 2023

This episode was written, edited, and produced by Colin Gioia Connors.

Theme music used with permission by Kristján Hrannar Pálsson.