What are the dangers of radicalization? Bjørn Westlie is a Norwegian historian and journalist best known for his reporting on Norway’s history of antisemitism, and he has been a driving force for elevating Norway’s Jewish history. Bjørn visited the UW to discuss his 2008 book, Fars krig [My Father’s War], recently translated into English. Bjørn’s book deals with his father’s past as a member of the Norwegian Nazi party and a volunteer soldier in the Waffen-SS during World War II.

TRANSCRIPT

Colin Gioia Connors: This episode engages with the legacy of antisemitism in Norway and contains descriptions of violence from the Holocaust. Please use discretion.

Were you and your father close?

Bjørn Westlie: [*emphatically*] No. [*pauses*] When I was young I was on the left side, I would say, the very left side during the Vietnam War and stuff like that. And he hated that. For many years we didn’t have any contact. So, yes. But we had a friendly tone— a friendly tone when he died. But one of the worst things about him was that he was so cruel and evil against my mother. So that was one of the things I could never— I could never really be friends with him because of that. But my mother died ten years before him. He was— The biggest problem—my father—is that he was really an intelligent guy who could be something else, he could be really something— he could have been everything. But he threw away everything with his leaning to the Nazi party.

[*Intro music starts*]

Colin: Welcome to Crossing North: a podcast where we learn from Nordic and Baltic artists, scholars, and community members to better understand our world, our communities, and ourselves. Coming to you from the Scandinavian Studies Department and Baltic Studies Program at the University of Washington in Seattle, I’m your host Colin Gioia Connors.

[*Intro music ends*]

Bjørn Westlie is a Norwegian historian and journalist who is best known for his reporting on Norway’s history of antisemitism. His reporting in the 1990s on the Norwegian-led looting of Norwegian Jews during World War II led to a reparation commission that awarded Norway’s Jewish population 350 million kroner in 1998 and established the Norwegian Center for Holocaust and Religious Minority Studies. Bjørn’s most famous book, Oppgjør i skyggen av Holocaust [Reckoning in the shadow of the Holocaust], was published in 2002 and recounts the history of this looting and the reparation process.

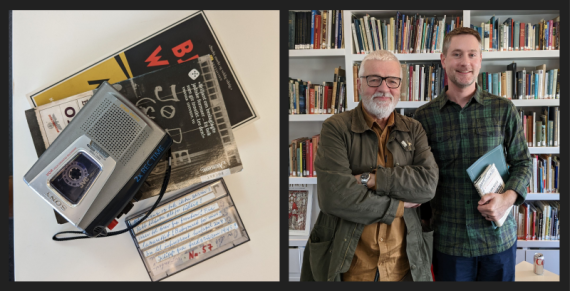

In 2008, Bjorn wrote a book about the Norwegian soldiers known in Norwegian as the frontkjempere, who volunteered to fight for Nazi Germany in the Waffen SS. One of those soldiers was Bjørn’s own father, Petter. That second book, Fars Krig [My Father’s War], was recently translated into English by Professor Dean Krouk at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and published by the University of Wisconsin-Press. During a book tour in Seattle last fall, I sat down with Bjørn and interviewed him about that book.

Bjørn: Well, it started with the article in 1995, I started it when it was the 50 years anniversary for the 50 years after the Second World War. And I knew that every newspaper would write patriotic stories, and [*satirically*] “All the Norwegians fought the Germans, and we are so proud about that, and…” So, I wanted to tell how Jews in Norway also were robbed by Norwegians, by banks, and insurance companies, and that people that were not Nazis that sent them with the trains and with taxis to the harbor in Oslo where they were sent with ships to Auschwitz. That was the start of it, and that was the important story, and now— So it's— [*long pause *] It’s been a task. Before this the Jewish story during the Second World War was not a part of the Norwegian story about the war, and now it is. So I've been— I have been a driving force in changing the history of the Jewish history in Norway. And it's— Why should a kid from a Nazi family do that?

Colin: You mean yourself?

Bjørn: It's myself. And that's the questions I always have been asked, and I think that it's not a good answer because it's— I never thought it myself. It was not because of my father, but it was because of something I found that could be interesting and also important in a way. So, from that I started to write more books about antisemitism in the 1930s, antisemitism during the Second World War, in newspaper, and you know. Yes. Most important in that, in the development as an author— 2002 this book about how the antisemitic or anti-Jewish stories in Norway still existed. And that was a book in Norwegian, it's called Oppgjør i skyggen av Holocaust [Reckoning in the Shadow of the Holocaust]. it's— Someone, somebody I know —Many people think that this is one of my best books— My best friend, he said to me after that book was published that, “You have to talk to your father before it's too late.” And then my. oldest daughter said also, “You have to talk to your father, you have to talk to Petter before it's too late,” because some years before that we had a telephone conversation that ended in a break. It's because my eldest daughter at that time was going to confirmation in Norway. It's a ceremony and it's a course that you have to go through, and then you also learn about different religions. And when he heard that they also learn of the Islam religion, then he was crazy because he hated Islam. So that's the way it started that— the break up with us started.

Colin: During the years of silence leading up to 2003, Bjørn’s father Petter began recording messages to his son in private on a tape recorder. He recorded 57 cassettes in total. Bjørn writes in My Father’s War:

“At home in his tiny apartment, my father amassed large piles of newspaper clippings, on which he wrote comments by hand. Much of it had to do with immigrants and politics—and World War II. He was alone, with no one to talk to, so he talked to himself using a simple tape recorder. A tall stack of cassettes gradually formed as he continued to mull over the same issues from his past. He was the one, not me, who finally reached out. … I listened to some of the recordings before setting them aside. They were letters to me in his voice, and it was all too difficult. He told me about certain parts of his life story, about his youth in the 1930s, the outbreak of war and his time as a volunteer soldier in the SS during the German invasion of Ukraine in 1941. But also about his disappointments, betrayals, and feelings of despair. The shoebox stayed in a plastic bag in the closet for a long time. Then one day, I took it out and started to listen, hour by hour. Slowly, I began to see my father in a new light. I started to dream about him—and tried to imagine what his life was like” (pp. 4-5).

Bjørn: The first time I started to listen, I started to cry because he said to me, “Bjørn, listen to to me. Can't you listen to me? Can't you listen to me?” And then I heard the voice of an old man that was wounded. He was longing for someone that he wanted to speak to: “Listen to my history.” But at the same time, he was [*emphatically*] so racist. He was an extremist, right-wing extremist. But the one thing that was the problem for him was the story of the Jews, because his mother was very Christian and she always told him about the Jewish history. But that— but that didn't stop him when he wanted to join the army, the German army, and to invade Russia. The the problem for him was what happened to the Jews. And after the war there were, there have been people like him, men, old men like him. They had their own club and they met in Oslo every week, every week on Wednesday. And my father was a part of that for a time. But when one of the— one of these guys was going to be buried, on the way back home, my father in the car starts talking to the other ones and starts talking about the Holocaust of what happened to the Jews. And then there's the other guys in the car said, “Well, there is no Holocaust.” And then he broke with them. He didn't want to be a part of that anymore. So that was a good sign. But that was not until 1980s or something like that. So it took a long time. But he died as a racist.

Colin: Well, could you tell me a little bit about his background and the time period that he grew up in?

Bjørn: I say, he grew up in a small city, and then there was a weapons and munitions factory there. He quit school and started to work there. He was very, very interested in sport. And in 1936, when Germany had both the winter and summer Olympics, he listened to German radio. And the Social Democrats and the left side, they didn't want that Norway should be a part of that Olympics because it was a Nazi propaganda fiesta. He hated that, the fact that they didn't want to be a part of it. But Norway did very good in the both the summer and the winter Olympics. And Sonja Henie who was the big skate dancer at that time, she won of course the gold and she raised her hands like the Nazi do when she saw Hitler up on the tribune. So they started there. And then in 1939, the Soviet Union attacked Finland, the so-called Winter War. And then he wanted to join the—a lot of Norwegians wanted to help Finland—and he wanted that, too. But his mother stopped him. At that time he was not a member of the Nazi Party, but in his small little town there were many of the young boys with their fathers that were engineers at the factory [who were members of the Nazi party], but he didn't want to join them because they were upper class. So he wanted to be not together with the upper class guys. And then in 1940, when Germany attacked Norway and invaded also their little town, he cried. He didn't like that because they killed people around Raufoss (the name of the town), people that wanted to stop them with their own guns. And they were killed, of course. But three months after that, he changed his mind and then he joined NS, the Nasjonal Samling, the Norwegian Nazi Party. And from that point he was a supporter of the German invasion and Germany. So in 1941, it was January, the Nazi leader in Norway, Vidkun Quisling, the traitor, he wanted that all young men should join the Waffen-SS. And my father and some of the friends of him, they joined the Waffen-SS. But they didn't know where there should be soldiers at that time. But then he went down with many other Norwegian guys, they went to Austria where they were trained as SS soldiers. At that time they were, Germany, they were still in a pact with Soviet Union, but that was broken in June when 3 million soldiers invaded the Soviet Union and my father was a part of that. And his regiment, they were sent to— went from Poland into Ukraine.

Colin: So for listeners who might not be familiar— the frontkjempere who are on the eastern front, the Waffen-SS, took part in atrocities, war crimes, murdering hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian Jews. Is this something that you ever confronted your father about? Did he talk about this in his tapes?

Bjørn: I asked him—and that is also in the book—”How many Jews did you kill?” Then he starts to cry. But you have to be— I mean, yes, also these Waffen-SS soldiers killed also, of course, Jews and others, but there were other regiments that were German, other regiments that had the job to really get rid of the Jews. So it was, I mean, everyone killed Jews and Ukrainians and resistance [fighters]. But when I asked my father about this with the, “How many Jews did you kill?” He said that, well, the Ukrainians pointed out where the Jews were. But it was not only that, because all the way, all the route where my father went, which I followed for 100 kilometers or something like that, and they killed, killed Jews. Everyone who tried to resist were killed. They killed kids and everyone. And you know, the Norwegian fronkjempere, which they were called, they had gotten the proposal that they should get a farm in Russia after the war, a big farm. And one of the thoughts I have in my book is that I, if that really had happened, I might be a farmer in Ukraine.

Colin: You told me before that there was an alternate title for the book: “The Little Wooden Box From Ukraine.” Could you tell us about that object?

Bjørn: Yes. When I grew up, there was always a wooden box carved with decorations, very beautiful. And my father had that on a table, TV over there, and the table. And he had his chair and his pipes and his box, and he had his tobacco and pipes in the box. So I remember the first time I asked him, “What is that?” “Oh, well, that is something I got in Russia,” he said. And much later I found out that he had not been in Russia, but in Ukraine. So, that box was an object of desire for my father, and it also became an object of desire for me because it was a concrete example of what he took from Ukraine. So, when I went to Ukraine for the first time, I took it with me and I just, “What kind of box is this? Is it true that, could it be that someone had given that to him?” But when I came to Lviv, there's a museum there and experts on that kind of thing, and I gave it to them in order that they could describe for me what kind of box it is. And very many [people] had that kind of a box, but they had money and jewels in them. And no one would have given my father that kind of a box because it's old and it's very important for Ukrainians. And you know why? When I had this together with someone who can help me interview people in Ukraine and a car, we drove along the route that my father also went, and I showed that box to old people. And everyone [said], “Oh, yes, yes, yes, yes.” They told me also that no one would give you that. They said, We digged, we made a hole in the earth to hide them when the Germans came.” So when I was there I called my father: “Father, now I know you have stolen it. You stole it. You stole it.” And he didn't want to answer me.

Colin: Did your father ever face punishment after the war?

Bjørn: When he came back to Norway in 1945, when the war was over, he was sentenced to, first, imprisonment, then in the labor camp, altogether 2 1/2 years. But he also lost his civilian rights, he couldn't vote. That was for 12 years. So, he was so angry about that. And he couldn't come over it.

Colin: Do you think that your father's sentence of 2 1/2 years of prison and 12 years disenfranchised was just, or enough?

Bjørn: No, it was not enough. But I don't know whether a longer sentence would turn out that he would understand more or excuse what he had done. But, I mean, for a normal person we will understand, if you dress into the occupiers uniform, you must understand that you are doing something— that you are a trader. I mean, and then supporting their war in another country? I can't understand why he could actually do that! He wasn't forced to go to the war with the Germans. He was not forced. He was voluntarily. That's the difference. What could I do if I was forced to something? Maybe I could kill someone. I don't know. I don't think so. I hope I don't, I will rather die than kill someone else. But I could never voluntarily do that, what he did so. So, that's the difference.

Colin: Why do you think that you became such a different person from your father?

Bjørn: It’s because I'm normal. He was an extremist, became an extremist. That's the problem with extremists. We have a lot of extremists in Norway. And a lot of extremists in the U.S.— more than in Norway, I think. You know, extremists are going to do whatever! Trying to stop the parliament— or trying to stop democracy. They're willing to do everything, they’re crazy! I'm just thinking I'm so happy that I'm not him [*slowly for emphasis*] because I have learned that it is so, so dangerous to be a believer— a believer and don't listen to other people. That's something that's the crisis also in our world today.

Colin: Well, reading your book, I think one of the things that I learned from it is that it would seem like for your father and other people in his generation, that it was a process of radicalization, of listening to Hitler's speeches, of listening to German radio, of those views being transmitted also by people who are in the Norwegian press who are covering foreign news—and so there is a process in which one becomes more extreme. Do you believe that it's possible then for that— to be de-radicalized, to go from extremism to more normal?

Bjørn: I know it's possible, but I think it's rather difficult because then they have to break away from the friends, the others in the group. All these guys who have been sentenced after this, trying to overrule the democratic process in the Senate [the January 6, 2021 U.S. capitol attack]? They're not— I don't know how many of them has really understood what they were a part in. I'm not sure that they understand that this is, that this was wrong, or? I'm not sure. When people become extremists, I think it's rather difficult to change that. So, that's one of the problems in almost every country, and I think it's a very big problem in the U.S.

Colin: What role do you think your mother played in that you didn't turn out like your father?

Bjørn: Very important.

Colin: Very important?

Bjørn: She was absolutely not a Nazi. Her and her sister, elder sister—she helped the Norwegian soldiers when they were fighting against the German soldiers and not far from where they lived. And she also got a decoration after the war because she was a brave 19 year old— not really a nurse, but she was a nurse in a way. I mean, there were 450 Norwegian soldiers that were killed—voluntary, also, there was also volunteers, there—were killed when the Germans attacked them. And so she was together with them when they died, and she was also helping them. So she and my mother's father and mother, they were not on the German side. My mother, in 1940, she befriended Ruth Maier, who was a Jewish refugee from Austria. She had come to Norway. And she wrote a lot of diary articles and stuff. And she befriended my mother. And she wrote a lot of beautiful texts about my mother. She, Ruth Maier, was sent 1942 to Auschwitz. Killed. But she left her diary in Norway. And this diary was found and had been translated to Norwegian in 2003, and I could find the text that she wrote about my mother. And my mother was, in 1940, she was 16 years old, and Ruth was 18. And my mother, when she went back from that city where Ruth lived—my mother was there for some months—and Ruth gave her a picture of her with a sentence on the back of the photo, “From Ruth, to Agnes,” and the date. So I have the photo of Ruth Maier that my mother got from Ruth. And then I found that Ruth wrote a lot of beautiful texts about my mother. But by that time, my mother was dead, so I couldn't confront her with that or tell her about that. But, the problem with that— the problem is that [*pauses for dramatic effect, and then fluidly*] my mother was a friend of Ruth, Ruth told her that she had fled from the Nazis and she was safe there, my mother knew her history, but in 1943, she fell in love with a Nazi. [*pauses for dramatic effect*] My father. So that's— that's a story that's full of conflicts. So I haven't managed to write about it before. Because my mother, she, she had become, in a way, a traitor. Even though she was not a Nazi. But when they left and when they moved to Oslo and had an apartment there, he had the picture of Vidkun Quisling, the traitor, in the apartment. And when he went to job, my mother turned it.

Colin: Okay, so—

Bjørn: And when he come back, he turned it back.

Colin: Okay. Always this tension in the home.

Bjørn: Oh, yes.

Colin: And this is the home you grew up in.

Bjørn: Yes, but that was during the war.

Colin: Okay.

Bjørn: After the war, my father had Knut Hamsun on the wall, who also was a Nazi. [*laughter*] So yes, it's a very interesting thing. I haven't managed to write about it before.

You know, when I wrote this article in 1995, I wrote an article that was also presented worldwide about what happened to the Jews. And Austrian radio and everyone was interested in that story. And in The Boston Herald Tribune, they wrote two articles. And in Boston there was a guy who was from Norway, a Jew, that because his mother was Danish they managed to get out. And he had read that article about me and what I had done. So he had a friend in Sweden that he called, and his friend in Sweden called me on whether I could find out this guy's history. And I did that.

Colin: Yeah?

Bjørn: So that's a part of the book from 2002, Oppgjør i skyggen av Holocaust. So the history is a part of that, and the end of that book, there’s a conversation between me and this guy. And then he said, he said to me that he missed his father— because he was killed: “I miss my father.” Then I said, “I also miss my father,” I said.

Colin: What do you mean by you— you missed your father?

Bjørn: It meant that I—at that time I had no contact with him—and I missed, which also means that I don't have a father. I would love to have a father that was a strong— and, you know, something like— not a Nazi. But a good guy!

[*Outro music starts*]

Colin: Crossing North is a production of the Scandinavian Studies Department and Baltic Studies Program at the University of Washington in Seattle. Today’s episode was written, edited, and produced by me, Colin Gioia Connors. Today’s music was used with permission by Kristján Hrannar Pálsson. Links to his music can be found in the show notes for this episode or on our website. Visit scandinavian.washington.edu to learn more about the podcast and other exciting projects hosted by the Scandinavian Studies Department. If you are a current or prospective student, consider taking a course or declaring a major. You can find complete course listings for the Scandinavian Studies Department and Baltic Studies Program at scandinavian.washington.edu. Once again, that’s scandinavian.washington.edu.

[*Outro music ends*]

SHOW NOTES

Release Date: April 2, 2024

This episode was written, edited, and produced by Colin Gioia Connors.

Theme music used with permission by Kristján Hrannar Pálsson