Assistant Professor of Scandianvian Studies and Norwegian, Olivia Gunn, began her appointment at the UW in autumn quarter 2015. Olivia earned her PhD (2012) in comparative literature from the University of California at Irvine after completing a dissertation on Henrik Ibsen, Realism, and the French Symbolist theatre. She is originally from Seattle and was once a student in the department (BA in Norwegian, 2002). She is very happy to be home. What follows is an interview with Olivia by department Ph.D. student Liina-Ly Roos. Liina-Ly's research areas include Scandinavian and Baltic literature and film. She is currently focusing on literary and film representations of childhood and trauma of the Scandianvian and Baltic regions.

Liina-Ly Roos (L-LR): Which classes are you teaching this year? Which classes are you most excited to teach next year?

Olivia Gunn (OG): This year, I have taught or will teach intermediate Norwegian (Norw 201, 202, 203), Topics in Norwegian Literature and Culture (Norw 321, fall 2015), and Ibsen and His Major Plays in English (Scand 280, spring 2016). The topic for my Norwegian 312 course was “Motherhood and Fatherhood.” The students and I explored a variety of modern texts and films (1880 to 2015) that offer portraits of mothers and fathers. Some examples include Ibsen’s Little Eyolf (1894), Tancred Ibsen’s feature-length film The Great Christening (Norway’s first sound film, 1931), and excerpts from the first volume of Knausgård’s recent novel, My Struggle (2009). Students also gave weekly presentations on journalistic sources available online via major Norwegian newspapers and research sites, analyzing the contemporary rhetoric of parenthood in the country recently ranked ‘the best place on earth to be a mother.’

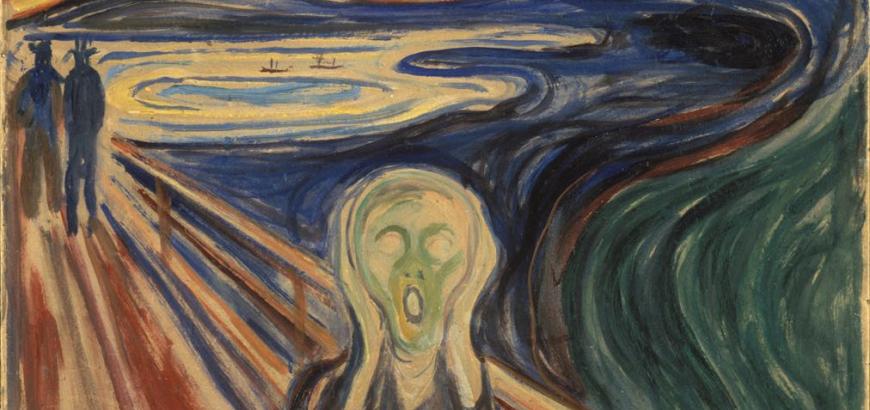

During 2016-2017, I am particularly excited about teaching Norwegian Literary and Cultural History (Scand 150). The theme for the course will be “nature as portrait of the human.” A common claim is that Norwegians have a close relationship to the natural world that surrounds them, and that this closeness is reflected in their art. In units on landscape painting, literature and film, ecophilosophy and the history of friluftsliv, black metal music, and more, we will ask, When humans represent nature in a work of art or other cultural product, what does that representation say about humanity, or about its maker and the community/era to which they belong? We’ll start by looking at Norway’s most iconic paintings, treating them as lenses for understanding how people differentiate themselves from, or project themselves into, an environment. What happened between 1848, when Adolph Tidemand and Hans Gude completed Brudeferd i Hardanger, and 1910, when Edvard Munch made Skrik? How had humanistic self-understanding changed, and why?

I am also looking forward to teaching Knut Hamsun and European Modernism (Scand 482, offered jointly with European studies) and The Norwegian Short Story (Norw 310).

L-LR: What have you been reading lately?

OG: During my morning bus commute (because my mind is sharpest at this time), I have been reading Stanley Cavell’s A Pitch of Philosophy, Jacques Derrida’s A Taste for the Secret (interview with Maurizio Ferraris), and Reading Boyishly by Carol Mavor. On campus and during my homeward bound commute, I read articles and chapters on Hedda Gabler and feminism or decadence for a chapter of my current book project, Ibsen’s Empty Nurseries. At night before I go to sleep, I am re-reading the first volume of Proust’s In search of lost time for a project – “Reading Knausgård, Feeling Proustian: Popular and Critical Approaches” – that I will present at the American Comparative Literature Conference in Boston this spring. I have also been thumbing through Tomas Espedal’s Gå (Tramp) and a dual language collection of poems by Olav H. Hauge titled The Dream We Carry.

L-LR: What compelling reason or example from personal experience can you give to a student to do a major or a minor in Scandinavian studies?

OG: Many deliberations over higher education (via politics, for example) involve calls for reassurance and accountability. This is both understandable, given financial realities, and paradoxical, given that success and innovation require willingness to take risks and a certain tolerance for uncertainty – in addition to hard work, planning, and luck, of course. If a student asked me, What can I do with a minor or major in Scandinavian studies, I might respond by asking What can’t you do with it, if you are also driven and creative? If you are interested in a Scandinavian writer or artist, historical period, socio-political model, or way of life, and if you are already lucky enough to attend UW, why not take this opportunity to follow your passion? As a student in Scandinavian studies, you can explore what interests you while gaining practical, sought-after experience (learning another language, developing greater global awareness, cultivating strong analytical skills, interacting professionally with others). Will it ever be safer to be creative and unconventional than during these short days – a mere four years! – of student life?

In terms of my personal experience, hindsight allows me say that it can be very helpful to stand out from the crowd on your CV and to be able to fulfill niche needs. My professional life, however, has taken a number of unexpected paths. While considering how I might answer this question, I thought of and looked up the expression “best laid plans of mice and men.” I didn’t know that it comes from a poem by Scottish poet Robert Burns called “Tae A Moose (To a Mouse)” (1875):

But Mousie, thou art no thy lan, (But Little Mouse, you are not alone)\

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o' mice an' men

Gang aft a-gley (go often askew).

The speaker in the poem has destroyed a mouse’s nest with his plow. As the creature skitters off, he envies what he believes to be its present-bound awareness, an instinctual way of being that compels the building of the nest but can imagine neither the plow’s strike nor the certain doom of winter approaching:

Still thou are blessed, compared wi’ me!

…

When – och! (ouch) I backward cast my e’e (eye),

On prospects drear!

An’ forward, tho’ I canna (cannot) see,

I guess an’ fear!

No calls for reassurance and accountability can rid us of foresight’s fear and guessing (or hindsight’s pain), but contemplation, curiosity, and courage are strong modes for negotiating this dilemma, and such humanistic negotiation can be pursued in the department of Scandinavian studies at UW.

L-LR: Your PhD is in comparative literature. Are you also using comparative approaches in your teaching or research, comparing Norwegian with works from other Scandinavian, Baltic or Western literatures?

OG: Yes, and I am definitely interested in continuing to cultivate comparative approaches. The Scand 482 course mentioned above is comparative in the classic sense, as we will be reading the novels of Knut Hamsun in the international context of European modernist literature. In a general sense, of course, all coursework in Scandinavian studies at an American university should be comparative. Through exploration of Scandinavian materials and contexts, students can learn to be critical of perceived or real cultural similarities and differences, adding nuance to the way in which they understand their local surroundings.

One of my central research pursuits is Norwegian cosmopolitanism. Perhaps because I have been abroad in Norway on many occasions, I am interested in depictions of Norwegians abroad – especially (but not exclusively) in Paris. I recently completed an article manuscript on the discourse of race and depictions of ‘exotic’ women in the last two novels of Cora Sandel’s Alberte trilogy (1931 and 1939), both of which take place in France. I hope someday to teach a course on ‘Europeans abroad in Europe,’ which would focus on novels about Scandinavian writers and artists traveling or living outside of Scandinavia, while comparing these novels with such works as E. M. Forster’s Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905) and Nella Larsen’s Quicksand (1928). A central question for this course would be, what did intra-European concepts of race and ethnicity look like in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and how do they differ from a contemporary American understanding?

I have yet to do research on Baltic texts or contexts, but I am excited to be in a department that can express, by its very structure, openness to comparative literature and comparative regionalism. I look forward to learning more from my colleagues and from graduate students working on trans-Scandinavian projects.

L-LR: Thank you, Olivia, for these inspiring answers, and welcome to the department! It is exciting to learn more about your research and teaching plans.